|

I drop down from a ledge and find myself in another enclosed area, unenterable buildings and impassable trees lining the path to the entrance for the next enclosed area at the opposite side. Between me and this objective are a smattering of waist high walls, some ammo and resources dotted around and four enemy NPCs on alert to insert some bullets into my body. Any gamer will be intimately acquainted with this setup. Let’s get murdery. My initial plan of stealth is thwarted, as it often is, when one NPC turns a corner unexpectedly to see me choking out their comrade. Naturally, they are shocked, recoiling for a moment before shouting, “She’s here!” so the other two are made aware of my presence. This whistleblower isn’t able to contribute much more, as they are quickly introduced to the shell spewing end of my shotgun. The remaining grunts, having seen another of their friends reduced to a fine paste, close on my position. Unfortunately for the first of them, this is a double barrelled shotgun. Now empty and with the final enemy taking aim, I rush to close the distance and melee with my lead pipe. However before I can strike the finishing blow, this nondescript cannon fodder NPC drops her weapon, falls to her knees, hands protecting her face and screams, “Please don’t kill me!” This isn’t how it’s supposed to go. Enemy AI are supposed to vainly fight you to the death, even after you’ve already killed dozens of their friends because, by God, they are going to be ‘the’ one that finally gets you. Sure occasionally you’ll have someone mutter a half hearted plea in a brief, intimate moment when you’ve snuck up on them before you incapacitate/kill them, but never anything this visceral, this desperate, this real. I’ve never seen this in a game before. Of course I still killed her. It’s a game, that’s what you’re supposed to do. If I’d let her go, what, was she just going to leave the area and gratefully live out the rest of her life? No, she’d either redraw her dropped gun on me or go and alert more baddies, after all I’m on her turf. At least that’s what I tell myself, I didn’t let her go so I’ve no way of knowing. Honestly after 20 years of gaming it was sheer instinct to take the fraction of a second to press Square and effortlessly launch the lead pipe into her skull. But, for the first time, that decision has stayed with me. The Last of Us Part II is all about how you are your antagonist’s antagonist. What is right and just for you is an unforgivable crime to those you perpetrate those actions on. And, without going into the bigger story, of which this constant shifting of perspectives is a main feature, it is present in even these smallest encounters. It’s the closest you can come actually feeling like you are fighting people instead of pixels. They all have names. They’ll call out for Colins, Sarahs and Zoes, both when they find their body (you just killed something with a name) and to periodically check in. This one in particular was such a small addition but made so much sense, unlike most other games where enemies follow their pre programmed pathing, completely unconcerned that the bustling crowd of comrades they were surrounded by but moments ago have mysteriously vanished, thanks to your spree of stealth takedowns. Of course other games have this, notably the Batman Arkham series as they get more terrified as their numbers dwindle, but usually only when they stumble upon a body, here they are proactive in sticking together and working as a team to hunt you down. *minor spoiler paragraph*

Even the dogs have names. When I took out a dog from range with a bow (there are no good boys in this game while playing as Ellie) its owner upon discovery cried out, “Oh my God, they killed Bear! They killed my dog!” A few chapters later in a flashback scene, I encounter the same dog called Bear, sitting happily as I scratch his ears. Since my first encounter with Bear was from ambient dialogue, this is a connection not every player would get, but one that adds so many extra dimensions with one throwaway line. *minor spoilers over* This extra level of immersion also works to The Last of Us Part II’s detriment though, as it is only one faction that has these unexpectedly human reactions. The others, the Infected - zombies that only bum rush you with no concern for their safety or other Infected - and a religious cult who are far more stereotypical in their belligerence and AI aggression are much less interesting to fight, though there are large periods of the game where they are the only enemies, and it’s at these points where the game starts to feel like a slog. The main theme of The Last of Us Part II is the rather unsurprising stance that violence is destructive. I have no issue that it makes that point by making me commit endless acts of violence, it’s a video game, what else are you supposed to do? This is a point Naughty Dog themselves have toyed with in the past, with Uncharted 4 having a trophy called ‘Ludonarrative Dissonance’ - the disconnection between a game’s story and its gameplay - for when quippy and personable protagonist Nathan Drake kills 1000 people, but as a player you should be able to distinguish between what is important to the story and what is there to make the game fun. That was what The Last of Us did so effectively in that random scene as an unimportant character begged for her life, it blurred the lines between Ellie’s story and the genocidal killing spree she commits for the telling of that story. Most video games, even the morally complex ones, tend to nullify that choice through gameplay bonuses. Bioshock gives you more resources for sparing the Little Sisters than killing them. Spec Ops: The Line gives you much needed ammo for executing downed enemies, so there’s little reason not to trigger that brutal kill animation. In The Last of Us I gained nothing for killing that pleading woman, other than the certainty that she could not then take up arms against me again. At least, that’s what I tell myself.

0 Comments

Of all the books I read in primary school, from Maniac Magee which introduced me to the concept of racism to Flat Stanley, about a kid flattened by a cork board, one has stuck with me more than the rest. And I didn’t even know its name. Actually that’s not quite true. We never read the full book, only an extract of it, and it’s the image from that extract that stayed with me. There was a boy and a talking dog, who were running in the forest. The dog kept running into all the trees because, while he could see the tree behind the one in front, he could never see the one in front. As a fairly literal child, this blew my tiny mind. “How could he not see the one in front? He’d have to look through the tree to see the next one??” Many, many years later, I finally got the point, that you can’t just look forward or plan ahead if you don’t live in the moment. My god what a revelation. I asked around and a friend, who had been equally affected by the book, was able to tell me it was, as the title of this blog suggests, Norton Juster’s ‘The Phantom Tollbooth’. I chased it down and if I was flummoxed by the running into trees (which wasn’t the dog but a floating boy called Alec) then I’ve no idea how I’d have handled the rest. It’s wild. Both literal and whimsical, literary and visually mesmerising, giving embodiment to idioms, making the abstract literal and with a delightful penchant for puns, all through incredible characters on a simple journey that any child should be able to follow (though obviously not this one).

In fairness if I’d read from the start perhaps I would have geared up to the concept. It starts in the real world, with a boy, Milo, who is bored of learning. The opening few paragraphs are some of the best I can recall in immediately establishing a character. “There was once a boy named Milo who didn’t know what to do with himself - not just sometimes, but always. When he was in school he longed to be out, and when he was out he longed to be in. On the way he thought about coming home, and coming home he thought about going. Wherever he was he wished he was somewhere else, and when he got there he wondered why he’d bothered. Nothing really interested him - least of all the things that should have.” If Milo were older he’d be getting sent to a therapist to check for depression. That listlessness and disillusion is something I’m sure we’ve all experienced, and sets him up perfectly for the journey into the wonder of learning and how there’s magic in everything around us. From the start of his journey, where he literally gets caught in the doldrums, a grey, boring place, he goes on to learn from the whole Kingdom of Wisdom, from words and numbers to perception and logic. Some are brief diversions, like the Island of Conclusions, whereas others are larger subplots, like stealing sound from the Soundkeeper and, my highlight of the book, Chroma the Conductor, whose orchestra brings colour to the world. The plot is a classic fairytale, saving the princesses Rhyme and Reason to restore sanity to the kingdom, but, as I learned much too late, it’s not about the destination, it’s about who you meet and what you learn on the way. There are so many incredible characters, from the funny, like the Dodecahedron, to the thoughtful, such as Faintly Macabre the Official Which, to the genuinely quite unsettling demons that live in Ignorance. Some of them might go over a kid’s head, but there are others which kids will get more out of, such as eating your words. Also Jules Feiffer’s illustrations do terrific work of bringing extra life (and honestly, clarity) to such bizarre concepts. I wish I’d read The Phantom Tollbooth in full when I was younger, but as an adult, it’s funny, clever and surprisingly deep in many places, and also a relatively easy read. It’s one that will stay with me, and now I have plenty more to ponder over than just those bloody trees.

Is it just me or was there not as much hype around the Super Bowl ads this year? Sure there were the usual headlines of millions of dollars being spent per spot, but the whole thing felt a little more rote and by the numbers, no real surprises standing out with all the brands that, in their excitement, couldn’t wait until the game and released their ads early. Anyway, I hear the game was better this year at least.

Budweiser Following some recent efforts of remaking their old ads, Budweiser thoroughly update their famous ‘Wassup’ commercial by replacing noughties dudes with twenties smart devices. The core concept is great, robotic voices eerily replicating casual conversation, but the rising ridiculousness as more devices from toothbrushes to kamikaze Roombas are brilliant at ramping up the comedy. The public safety message tying in Uber at the end is a bit of tonal whiplash, but overall a fun ad that hits the nostalgia and funny brain matter.

Cheetos

Have chosen the ad’s teaser (a concept I normally hate) for this entry, but the joke never gets funnier than that initial eureka realisation. MC Hammer sits at a piano, humming a new tune, when suddenly the Cheeto product’s greatest drawback becomes inspiration for a multi-platinum song. Fantastic example of flipping a negative into a positive on Cheetos’ part, and a perfect example of celebrity tie in that suits the brand perfectly.

Little Caesars

Sliced bread has had it too easy for too long, or so say Little Caesars. Sure it hits every cliche in the book, but the execution between production design, editing and Riann Wilson’s megalomaniac performance really tickled me. That it took Little Caesars to finally cause everything to crumble over at Sliced Bread HQ is perhaps a stretch, but this ad left me for one in the mood for pizza.

T-Mobile

As someone else with a mother who loves a phone call, this felt very relatable. Basically a product demo ad, with a big USP slapped all over, but the performances and twist of who could be using the new service did a good job of getting that message across clearly. T-Mobile works anywhere - and maybe not ideally for you - at any time.

Pringles

Think Pringles made a really brave move here, as this is really more of a Rick and Morty piece of content than for Pringles. That’s probably why it works, doubling down on Dan Harmon and Justin Roiland’s zany, cynical sci-fi tropes, even going so far as to make Pringles the ‘bad guy’ in the scene, and plus the internet loves Rick and Morty, for good or ill. Sure it doesn’t really have a resolution, but with over twenty Pringles references in 30”, they’ll be considering it job done. It’s in New Orleans. By the Mercedes Benz Superdome to be precise. The statue is called Rebirth and was sculpted by Brian Hanlon. It’s of a man who’s name I had to Google. I even discovered it by accident. Myself and two accomplices were in New Orleans and taking in the sights. Looking for a chance to sober from our exploits in the French Quarter, the Superdome was something that even being from 7,000km away we had heard of, so we went to check it out. It’s a very impressive structure, set back high on a mound, and absolutely huge. It was January and the Saints had been eliminated before the playoffs, so we only saw the outside. And no one else was around. Facing the front stand of this mammoth stadium we looked around for a visitors entrance or gift shop. None was apparent. Let’s just walk around it and we’ll stumble upon something, we thought. We turned right and set off. Have I mentioned how massive it is? Well, after about twenty minutes and walking 350° of the circle we finally found the (unmarked) gift shop. The clerk, friendly though he was, made no attempt to hide laughing at us, the funniest thing he’d heard that year, pointing out the dumb Scottish boys who walked all the way around the stadium to every other customer in the store. Awright mate! Maybe if you had a sign outside? But I’m glad we did go the wrong way. Not only because it meant we saw the ridiculously named Smoothie King Stadium tucked away around the back, but we also stumbled upon the Rebirth Statue. It was 2006. The New Orleans Saints were playing their first game in New Orleans in almost two years, after the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, which almost brought the city to its knees. There was talk the area would have to be abandoned, left to become the biggest ghost town in the world. But despite it all, the city pulled through, and was beginning the long road to recovery. Their opponents that night were division rivals Atlanta Falcons. Just over a minute into the game, the Falcons are on a 4th down so go for a punt. These are standard plays and, with my limited understanding of American football, pass without much drama. However this time as the kicker, Michael Koenen, receives the ball and drops it to kick, a Saints player, Steve Gleason, breaks through the Atlanta lines, throws himself in front of Koenen and blocks the kick. The ball breaks for New Orleans who score the touchdown and the 75,000 crowd erupts. https://youtu.be/MIGgBhNtOP4?t=42 New Orleans, beaten, battered and bruised, was still alive, its spirit unbroken, its determination intact. It was an experience unique to sport, a unifying, cathartic moment seen by the world that galvanised an entire city. New Orleans returned and recovered its status as one of the most vibrant and unforgettable places in the world. The Saints went on to have their best season to date that year, and many put it down to that moment, the blocked kick, that marked New Orleans’ rebirth. And as if Steve Gleason wasn’t inspiring enough, by the time the statue was unveiled in 2012, he had been diagnosed with the terrible disease ALS, however had become a campaigner to raise awareness of ALS, and, unbeknownst to me, only three days after I write this is due to receive the Congressional Gold Medal for his contribution to the cause. But that’s not why it’s my favourite statue. It’s my favourite because, as well as marking Gleason’s heroic block, they have also included Koenen, the Atlanta kicker, in the statue, forever immortalising his fuck up.

Imagine being Koenen in that moment. 75,000 screaming fans going berserk, and forgetting the wider symbolic resonance of the play, knowing that you’d messed up a pretty basic play. I wonder if he thought, “Damn, I made a right arse of that. Hope no one ever goes and builds a statue of this.” That to me is art at its best. It can encapsulate moments of such intense emotion, ecstasy, pride, inspiration and hope. But if you can also capture some humour and an eternal “Get it right up you” to your local rivals, all the better. It's simply beautiful.

With the year 2019 turned out to be, I don’t think many minded when Christmas arrived at the earliest possible moment - November 1st the ads and supermarket packaging appeared - as a welcome distraction while the world burns around us. So let’s huddle round and roast marshmallows on the cindering remains with these, my favourite corporate manufactured emotion manipulators of the year.

Apple A good year for Apple this Christmas on the ad front. This short film tells the story of a family going to spend Christmas with their widowed grandfather and all the bickering, laughs and tears it entails. The attention to detail is brilliant, the characters’ thoughts alluded to but unsaid, everything tying together to become important in the end and including the product as naturally and unobtrusively as possible - even the lazy parenting is understandable. And only those with black holes for hearts won’t be moved by that score from Up. I’m not crying, you’re crying.

Apple iPhone 11 Pro

Polar opposite from the wider brand ad, but if the brief was to show how amazing the camera on the iPhone 11 Pro is then consider me sold (metaphorically). Exciting, energetic, epic, it covers ground rarely seen in Christmas ad space by making an action sequence and putting you in the heart of it.

Aviation Gin

While the ad itself is nothing really to write home about, the means by which it was distributed, by marketing maestro Ryan Reynolds, makes it one of the year’s most memorable. Within a week of Peloton’s contentiously received offering, they sourced the actress and quickly fired out a response, which must have gained as much traction from Twitter as the original did in its whole paid for campaign (not that Peloton will be losing sleep over it, the amount of earned media over this debacle will be enormous).

Mercedes

For my money the funniest ad of the year. Simple premise, expertly directed to ratchet up the tension with two spot on performances. The kid, unlike so many others this year, stays the right side of precocious without becoming punchable, and ties in to the brand line of “For those who never compromise.” I still laugh every time I watch it (“Timmy… Timmy! Wh-What are we doing?”).

Morrison’s

While the other supermarkets tried, and in my opinion failed, to out dazzle each other with big ideas and bigger budgets, Morrison’s did something completely different. They started with a well executed, if forgettable food porn ad, but then went one further when two colleagues came to them suggesting they make a film about something they do year round, giving food to a local food bank. The colleagues shot and appear in the ad, and the genuine generosity and authenticity will do more to endear them to whoever sees it (admittedly, I suspect, not many) than a CG dragon ever could. Or rather, my judgement of morals in video games. Short answer, they’re great, nothing is more welcome than encountering a great moral crisis in your downtime. More specifically this is my judgement on how morals are measured. Recently I’ve been catching up with a few renowned games I missed on their first outing, which were highly praised for the maturity of their storytelling and depth of their decisions, with morality baked into their core. They were massively different games, but here’s my thoughts on how they dealt with the moral choices they made you grapple with. The first one is Catherine, or rather the 2019 remaster of the 2011 original, Catherine Full Body. The game invites you to escape your real life troubles and play as a borderline alcoholic experiencing an existential crisis who cheats on his girlfriend (escape?!). It is, essentially, a block puzzle game that chose as its packaging a mature look at adult romantic relationships. You play as Vincent who cheats on his long term girlfriend Katherine with a mysterious, attractive woman named Catherine. However in the re-release Full Body, there is a third character, Qatherine (Rin) added, and not as an afterthought, but thoroughly integrated through the entire game, in re-recorded dialogue, inserted in original scenes etc. Though this inclusion is impressively done, I do feel it somewhat spoiled the experience. Spoiled is the wrong word, and without having played the original I’m speculating, but Rin does seem to unbalance the game. The base choice was initially between Katherine, a stale relationship perhaps past its sell by date, built mostly on expectation with an overbearing partner (she scolds your drinking and even says she’ll be looking after your money when you get married) and Catherine, a free, young sex maniac who offers excitement and sends kinky pictures, if a bit domineering. However Rin appears to offer the best of both, developing a strong emotional connection, supporting you without impinging on your own freedoms. For the majority of the game she is presented as the obvious choice, removing the moral ambiguity, and gets more screen time than both original romantic options, leaving them both feeling sidelined. As to how morals work, there is a handy moral meter that changes depending on conversations you have in game or texts you send to Catherine, Katherine or Qatherine. If you choose to help or be nice to a character, it goes right for good morals, if you choose to not help or be self indulgent, it goes left for bad. There are also specific moral questions you are given after solving every puzzle with your answer moving the meter one way or the other. This in my view serves to simplify or nullify the ambiguity of the questions you’re answering. Some of the questions just don’t lend themselves to this binary right or wrong options, for instance answering “Do you believe in an afterlife?” with “Yes,” gives good morals and “No,” gives bad morals. Can a question of that magnitude really be boiled down like that? Sure the game calls the two sides of the meter ‘Order’ and ‘Chaos’, but if you’re human (a fair assumption) you are conditioned that ‘Blue’ - Order means good and ‘Red’ - Chaos means bad. Another question was “Do you prefer Big Budget Blockbusters or Small Indie Films?” What has that to do with Order and Chaos? Aren’t most big blockbusters by nature made to be safe, while indie lovers can also be total riots? On the whole these choices don’t make too much functional difference, changing only what ending you get (which can still be with any of the three women) and Vincent’s internal thoughts. This is a clever reframing, as it means you aren’t so much playing as him but guiding him, setting him on a path with these character revealing questions. My issue is trying to quantify such thought provoking dilemmas on a left - right barometer. If you choose the Rin route, obviously added years later, the questions are also much more simplistic with obvious ‘right’ answers, even when they should be far more complex. One excellent mechanic was after answering each question, it would show a pie chart of what real men and women in their 20s and 30s answered, which could be very revealing, but it showed on these latter Rin questions the players’ choices moved more and more out of sync with what real people actually answered. In a game about true love, “Would you be able to accept any secret your lover has?” is always answered “Yes,” but in real life, is it really so black and white? The second game I played was 2015’s Undertale, a side scrolling role playing game where you play a child who falls into a world of eccentric and often well meaning monsters. What made it famous was its genre bending approach in that it judged you not as the main character, but as the player. If you chose to kill everyone, it would ask you, directly, what in you made you behave this way, and if you only killed one it would ask why you stopped short of killing no one. In fairness it had an easier time handling its morality as you were judged by your actions, not words. There are three ‘main’ endings, Pacifist for killing no one, Neutral for killing some people (the one I got upon accidentally killing a couple) and Genocide for killing everyone. What the game does best is how your actions are integrated into the story, and while other games merely have characters react slightly different as the core experience remains fundamentally the same, Undertale’s story changes vastly depending on your actions. You feel they have real consequences, for instance in a Genocide run, latter game characters are absent as they have run away and are hiding from you. These positions aren’t immediately visible on screen, there is no bar checking in on your morals as you go, making your choices feel more natural and dynamic. Of course you can still judge one ending to be ‘good,’ sparing everyone and the other ‘bad,’ killing everyone, but what Undertale did very well that other games with similar all-good and all-bad paths often neglect is the grey bit in the middle. Usually in split morality games where you are regularly given good vs bad choices (Bioshock, Infamous, Mass Effect, Dishonoured, Mafia III etc) it makes sense to stick to one path entirely, as doing so rewards you with either high tier abilities in game or trophies/achievements for completing the game in one of its polar opposite ways (a sneaky con to make you play it twice and avoid trade ins). There is little point mixing between both and sitting in the murky moral middle, which is where most of us live in real life. Undertale at least doesn’t lock you out of paths or leave you missing out if you accidentally kill or spare someone, depending on playthrough. I inadvertently killed a character early in the game (and felt dreadful about it, since they purposely did not fight back, another example that challenges how you think a game is supposed to play), but instead of reloading a previous save I persisted, towards an end that incorporated my errors without feeling diluted, and meant I could play the rest of the game without stressing about sticking to one rigid path. The final game and absolute moral sickener I played was Lucas Pope’s 2013 Papers, Please. You are a border guard for a Soviet-esque communist dictatorship and review passports, visas, work passes etc of the people entering your country. There are no moral meters here and few hints of a ‘good’ ending. People come, you examine their documents, and if they are in order you let them in, if they are not you deny them entry. However you don’t have to, you can reject people who might cause trouble despite their papers being fine, or admit people who beg you for entry, the only penalty being 5 Credits, the in game currency. But you have a family, and they need your support. At the end of every day you can choose to buy food, heat or medicine for your family, and if you don’t, they will die. The game’s pacing and increasing difficulty means you often clear just enough to take home (you are paid per inspection), and with penalties coming with natural mistakes as well, you are left with many tough decisions. Is it worth the personal cost to yourself by admitting a newly married wife with her husband when she has no visa? There are times it is easy, such as human traffickers or murderers, who you can flag for ‘Detention’, but what about the shady resistance group offering freedom and a better life for all, when you are up for inspection from the commissar? Once I was left having scraped enough to pay for a birthday present for my son, but was plagued by thoughts of the mother who spent her life savings travelling to visit her estranged family that I’d rejected as her papers had expired en route. There’s nothing wrong with doing the ‘wrong’ thing in a video game, indeed some games force you to, just look at Untitled Goose Game where the mission is to be the biggest dick possible. A less fun example is the final level of The Last of Us, I did not agree with what my character was doing, but was stripped of my choice if I wanted to finish the game. The decision of what is right and wrong should be left up to us as gamers, not a moral guide meter. Fallout New Vegas was so much more absorbing with its faction system instead of its karma meter, as you were to decide what was right and wrong.

Games inherently don’t know morals, they are just strings of code which can easily become arbitrary. One that still rankles me is the honour system in Red Dead Redemption 2, where, as since there are upper and lower limits which were capped before you leveled up, and as I always sat at the top level, I couldn’t add to my number yet could still easily lose it. This led to the bizarre scenario where I reached max honour by wiping out an entire chapter of the Ku Klux Klan yet immediately lost it again because on my escape I bumped into someone with my horse. Some decisions shouldn’t be reduced to numbers. Games are a form of escapism. For relaxing, stress release or tests of skill, but they can also be character challenging. Difficult decisions can be some of gaming’s best moments, often I’ve had to pause a game and put the controller down as I’ve weighed up the pros and cons of impossible moral quandaries, but it’s so much more powerful when you are left to process the effects of your choice yourself, or have it be left ambiguous - “Clementine will remember that” - rather than have the game tut at you and shake its head. It’s not angry, just disappointed. The moral of this blog is, giving us tough moral decisions can be great, but please, don’t judge us. I was recently asked to give feedback on a novel manuscript. On the whole I’m enjoying it, but since critical, forensic feedback is always more useful than an encouraging, “It’s good!” or “I liked the bit where...” here’s a brief list of some of the areas I was looking at when I fed back. Obviously all these are easier to see when not caught in the fog of writing, so if I’m guilty of any of these (which I absolutely am), please be gentle.

Nice to Meet You The book is about a large family and follows each of the members’ lives. Each chapter focuses on a different character as they splinter off on their own path, after an initial prologue which introduces the whole family. Nice setup, but obviously this means having to learn about a lot of characters at once. Initially this was as a paragraph each in descending order of age. Fine, functional, but for the opening of the novel could be a lot better. Can each character be given a mini-scene or an action/interaction/dialogue to introduce them? Do we need to meet every character in detail at once, or focus on a few and then open out to the rest as they become important? It put me in mind of the opening of the Godfather, which had a similar setup while also introducing the arcs, themes and plots throughout the rest of the story, as explored in this excellent article from Industrial Scripts. Flavours of Conflict Also mentioned in the article above are the different types of conflict, Internal (an inner character struggle or flaw), Interpersonal (a struggle between two characters) and External (a struggle against forces beyond the character’s control). Throughout the manuscript most of the conflicts were external, with the majority of the characters good, decent people coping with problems over which they had little control. This made them reactive more than proactive, and the beats of encountering a similar kind of trial more repetitive. More subplots with internal or interpersonal struggles would offer more variety and different solutions to different problems. Variety of Voices One of the main challenges of writing is creating realistic, believable characters, but just as importantly is that they are unique and distinct. Each character should feel like their own person, with their own view, attitudes and voice. I’m of the opinion a writer should be able to hold two opposing trains of thoughts simultaneously, otherwise all your characters would sound or behave similarly. Related to the above with most characters being good and decent with minor personality variants (this one is stern, this one is outgoing), with the amount of characters in the story there needed to be more distinction. Also each character will have many facets to themselves. How one behaves with their family would not be the same way they act with their friends, or a lover. This gives a good opportunity to explore different sides to the character with these different groups, and may help them develop or change their opinion on something to help further the narrative. Hitting the Same Beat There was one character in particular who, every time you met them, seemed to be crying or holding back tears. In each isolated incident, that was probably a fair response, but taken together and coupled with these occasions being the only times we met this character, they just seemed like a walking bag of tears. While an action may make sense in its context, the overall narrative has to be considered, and if the same thing is happening repeatedly, is the same note being hit too often? Exploring Options When planning a scene or chapter, there will be an obvious way to tell it, but rarely is it the best way. There were a couple of times in this story I wished a different route had been taken to twist my expectations, find new ways for events to play out that reveal new sides to these characters. How about if the character reacted this way instead of that? Is it more interesting if this character does this action rather than this one? What to Tell This story is a saga, which I admit I don’t have as much experience with as other story forms. Often what is as telling as the story told is the story untold. Choosing what scenes to write can really establish a theme or relationship, and others can seem so interesting you want them to be explored more. There were some events that were summarised in a paragraph that I wished had been expanded upon as the dramatic potential was so rife, whereas time was devoted to other elements that maybe weren’t so engaging. There are scenes that encapsulate big moments, but if the ending is a foregone conclusion does it need to be explored in depth? While other, smaller character beats can really help an audience connect with a character. Subtext Finally, and this must be the one most common to most writers, one I’m quite guilty of, is filling the story with subtext rather than text. Every writing book puts it up as one of the most important aspects, but it is one of the hardest to get right. Don’t say what everyone means, thinks or feels, find other ways to demonstrate it and let the audience figure it out for themselves. *Spoilers I want to like Peaky Blinders more than I do. The premise and setting is one of the most interesting on TV today. Everything from its costumes and set design to the cinematography and editing make it a technical marvel, and one of the best shows produced in Britain in many’s a year. The characters and acting are also a tour de force and it’s no wonder it has achieved the cultural impact it has, but there are just too many smaller issues, that over time have built up, to stop me from loving it. Season 5 sees Thomas Shelby (a near iconic Cillian Murphy) struggling with internal demons while he supplements his duties as head of the Peaky Blinders with that of an MP. Added to this are the simultaneous challenges of the Wall Street Crash, rival gangs seeking to usurp the Peaky Blinders’ dominance and a sinister politician who could change the course of the country’s history. But where most shows of its gangster ilk get stronger with each passing year, for me Peaky Blinders has never surpassed its opening season. The most obvious reason for this is the streamlined scope. The Peaky Blinders, named so for the razors they hide in their caps, are an upstart street gang in post-WWI Birmingham, where the main threats are a bigger gang boss and a police inspector closing in on them. In this most recent outing, as in the poorest season to date (Season 3), they are rubbing shoulders with some of the most influential and dangerous people of the era. Raised stakes are no bad thing, but it does sacrifice some of the rawness that were the show’s roots. It’s almost as if the show has become a victim of its own success, each year needing to outdo itself, but there’s one constant element which for me means the Peaky Blinders are never the underdogs the show tries so hard to paint them as - Tommy Shelby. After all these years he has become almost superhuman with his intellect and scheming. He even casually mentions that apparently he foresaw the Wall Street Crash coming. The show is so keen for him to be the genius antihero that they have removed all threat of him ever being defeated. I say this in the full knowledge that he “loses” at the end of this season’s finale, but that was not of his own doing. There is some mystery as to who foiled him (though not by the looks of it, any of the main antagonists), but for sure it was one of his associates or family who betrayed him, for Tommy himself never fails. This is where the show aims to reveal Tommy’s weaknesses, in his relationships with those closest to him. He is distant and often unappreciative of the people who have got him to where he is, but it is hard to empathise with him when he is equally closed off to us as viewers. He is shown, very obviously, to be having suicidal thoughts, personified by visions of his dead wife, but beyond that you never get much chance to see inside the man. Tony Soprano was so relatable as he had the same troubles and flaws as us, but Thomas Shelby is always indecipherable. You never see him formulate his plans, or have any semblance of a normal life, hell I forgot he even had children at points this season. He is always the enigma in the long black coat. This is a greater issue I find with the show, it often becomes too interested in being cool at the expense of story. It is a visual masterclass, however some of these don’t make sense. For example, there is a scene where Tommy approaches a scarecrow, only for a note to reveal he is standing in a minefield. The following sequence is brilliantly tense, as he treads his way back through the explosive ground (how did he get to the scarecrow no problem? Doesn’t matter), before his son runs into the field as well (why does he do that? Doesn’t matter, Tommy’s indestructible but his son may not be!). He catches his son in time and leads him away, danger averted. However he immediately marches back into the field with a machine gun, ignoring the seemingly now harmless mines and shoots the scarecrow and the mines, though not the ones he has now walked through three times. Was it cool? Yes. Did it make a lick of sense? Not one! This was the major issue of Season 4. It smartly took the characters back to their roots against a small scale, but believably terrifying force in Adrian Brody’s New York mafioso. He kills Tommy’s brother in the opening episode - holy shit! stakes! - gets in a room with Tommy and threatens that he will kill him only after he does the rest of his family. He then kidnaps his family, and doesn’t kill them, before making the shoddiest attempts at Tommy’s life, ignoring his previous purpose. Phenomenal setup, underwhelming payoff. Season 4’s antagonist also felt an organic development of the story, as a consequence to Tommy’s previous actions. The Season 5 antagonists though, of which there are plenty, seem to just be drawn from contemporary elements and then smashed together against the Peaky Blinders. Oswald Mosely, the real life British Fascist is the main villain, who Tommy decides to target unprovoked, though as many of the supporting cast themselves ask, why? Because he’s a fascist, and fascists are bad, and Tommy Shelby needs an enemy? He often treats Tommy with unnecessary antagonism, presumably to try and stoke the conflict. Same with the Billy Boys, they come from nowhere and then almost as quickly fade back to being no more than a name dropped plot device (side whinge, dreadful Glaswegian accents and the worst onscreen depiction of Glasgow - at the time bigger than Birmingham - as a single track country road). As for the other characters this season, none of them really seemed to develop since they all live in Tommy’s shadow in terms of significance. Arthur is squandering all sympathy by reliving the same storyline he has for the last few seasons, and it’s getting tiresome, Pol, again, is given criminally little to do. The show has also indulged in my pet peeve of any interwar British drama having to include Winston Churchill. Alfie Solomon is back, not through any sense of logic, but because Tom Hardy is so fun in the role. The main standout was Michael, who now backed by his clearly smarter wife Gina is looking positioned to become a major rival to Tommy in coming seasons.

That is once they resolve the loose plot points from this season, being the first one to not definitively end. It’s not an issue that they are building a multi-season storyline, in fact several of the issues I’ve griped about could be aided by having longer seasons, but it does mean this season feels pretty inconsequential, a lot of plate spinning for resolutions that we won’t see for another year. There is so that Peaky Blinders does so well, the camerawork (one scene where an entire bullet extraction was shot in one take was remarkable TV), the editing and its world building all deserve mentioning again, as does the often brilliant dialogue (“I’m glad I didn’t shoot you, it would’ve been a kindness.”). But then it misses too many opportunities to prevent it from moving beyond a good, stylish show to challenge the top tier of American gangster shows which at some point it could have done.

Recently I was working on two ads that, as deadlines would have it, were filming within a week of each other. Beyond the fact they were both shoots and all the similarities that entails, they couldn’t have been more opposite ends of the style spectrum. Now they’re both on air and I’ve had a chance to catch up on my sleep (20-year-old location-drama floor-runner me would be embarrassed), here’s a brief comparison of the two.

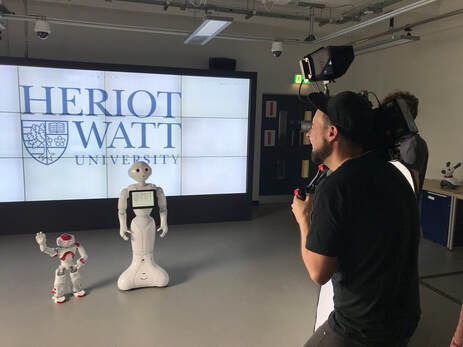

First up was Heriot-Watt, a university in Edinburgh who wanted to get more applicants for their courses, having not advertised as much as their competitors in recent years. The brief had different elements they wanted to promote, including their heritage, range of courses and employability. Their current campaign is “Be Future Made,” which provided a good kicking off point. The client also had a strong idea of the kind of adverts he liked, inspiring, emotional and voiceover led. After a round of scripts, it became a little bit of A and a little of B, then we were swinging into production. Heriot-Watt is an entire university and, therefore, huge. Meeting the client to discuss the script was so useful as it turned into a subterfuge recce, almost entirely informing the shot list. You never can know a client well enough until you get out and understand their world. We also firmed up the aims of the ad, to showcase the range of courses on offer - mostly scientific and engineering, but also including finance, social sciences and textiles, reference their international campuses in Dubai and Malaysia, and highlight the diversity of the students coming from a whole range of backgrounds. So, quite a lot to do in 30 seconds.

Time was always the concern on this job, trying to balance everything that needed to be included and in timescales that were not the most generous. Things that aided us were we obviously already had a location and in most cases it was pretty photogenic; Heriot-Watt had a group of student ambassadors we could use for filming, essential as we couldn’t have done it without them; and we assembled a good crew of seasoned pros able to work on the fly. To check the script was working I made an animatic from recce photos and internet images, along with my best epic VO, something I try to do for every job, and though quick, all was flowing fine.

In no time it was shoot day, a 06:15 call time to get to the location in Edinburgh. We had 10 unit moves around the campus to capture as many of the courses as possible, the shot list pruned from 40 to 25 shots and the production coordinator and runner had spent a day orienting themselves and making a movement order so we wouldn’t lose precious time getting lost in identical looking corridors like kids on the first day of high school. The shooting style had to be as light as possible. Handheld, battery powered lights and everything needed to be set up in preparation for us arriving. When shooting in a well lit area, we dispatched the gaffer as a makeshift B Camera for pickup shots of exteriors, particularly during dry spells as the weather, of course, was nowhere near as cooperative as on the beautiful recce. The staff around the uni were a great help, setting up experiments, coding programs we needed and teaching a student how to operate heavy machinery. Phil (prod coord) and Barnum (runner) were terrific at keeping everything running and getting the students I was looking for where we needed them to be, myself not being able to see them before shooting (thanks GDPR). On Phil’s pedometer he clocked over 34,000 steps for the day, over 30km. Not only did we get everything we were after, without having to compromise on quality, but we wrapped 10 minutes early, getting back into Glasgow at 20:30. With it all happening so fast it was hard to see the wood for the trees, but reflecting back that we got to film with lasers, lathes and a fist bumping robot, this was a particularly fun, interesting job. The client was a great help, throwing himself into it full heartedly, and I was delighted to hear that in the first week of running searches for Heriot-Watt increased by 600%. Plus I got to see it on the big screen (my first cinema ad) right where The Rock’s face would soon be in Hobbs & Shaw. Back pats all round.

Meanwhile, as all this was going on, another ad was in production for a client that has grown with us over the last 18 months, Carrington Dean. They were looking for a new branding ad that was to bring their new campaign, “Don’t let debt become your elephant in the room” to TV. For several reasons, timescales, the nature of the shoot and that I had only polished the script from someone else’s concept, I was to shadow the director on this one.

The idea behind this one was a woman in her house starts seeing elephants everywhere, as debt starts playing on her mind. Therefore pre-production was totally different, even discounting the lack of actual elephants. We had to do castings, art directing and location scouting, all of which had been provided on Heriot-Watt. This meant we had far more control over what the ad was going to look like, but also a lot of work in making it happen. For this ad the main challenge to consider was tone. We didn’t want debt to seem trivial or to be made light of, even though loads of elephants suddenly appearing could easily be made funny, while at the same time not making it appear scary or insurmountable. The director did this by casting an actress with good expressions and timing, without going too large or comedic, and aiming for a more absurdist style. Perhaps the most tangible difference between the two jobs was that while one was filming an entire uni campus, this was filmed almost exclusively in one room. While some of the crew was doing half marathons on Heriot-Watt, the only moving we were doing on Carrington Dean was from the living room set to the front door of the house we were using for some much needed fresh air; the 10 grown bodies, lights, smoke machine and summer sun (seems to always be nice when filming indoors…) creating quite the atmosphere.

To justify my presence on set, I appointed myself script supervisor, before also being asked to help as a 1st AD. This put me in the very contradictory position of saying, “Come on guys, we’re going to have to speed this up, we’re ten over, but also are you sure you got that, was the eyeline is maybe a bit off, should we do another one?” Being contained in one room meant more control over how everything would look, but naturally also led to procrastination and tinkering. Plus as this was one sequential scene, continuity was much more important, both for props and costume, but also the arc of setup, descent into elephants, and resolution.

As time got away, after spending more time on the key scenes/emotions, we started thinking creatively and logistically about what scenes were vital, if they could be cut/condensed, and if actions could be moved to where we already had a lighting setup. In a final deviation from my shoot the week before, we wrapped ten minutes over, both vastly different shoots having ended up filming around the same amount. Post production on was equally different. Heriot-Watt looked much like my original animatic (though obviously much, much better), whereas a lot of experimentation went into Carrington Dean. Since it was building a narrative, it needed to tell the story in a very strict, short timescale. Ultimately the script ended up moving around, with payoffs becoming setups and full sequences cut to create a more cohesive ad. The sound sessions had totally contrasting priorities too, Heriot-Watt requiring a lot of direction on the driving voiceover while Carrington Dean built a soundscape of elephant roars as the cherry on the metaphor of debt. Carrington Dean also got a great reception when it launched, the client telling us they had their busiest Monday/Tuesday ever (this from a company whose staff we made work weekends after a previous ad campaign - they must love us), and imagery from the shoot is popping up on billboards around the country. The client is lovely, and puts a lot of stock in our advice, so great to see them continue to have great results with us. It’s the old waiting on a bus thing, we might not have a shoot for months then two come along in a week. But what is always the case is the clients and the jobs are never the same, each one bringing its own challenges and solutions. The great thing about this job is you never know what will come across your desk. Next up I’m filming a toilet getting interviewed. I don’t really follow music. Of all the things to keep up with in modern life - movies, TV, sport, books, podcasts, video games - something had to give and for me it was music. It’s probably since I listen to it passively, having it on the background as I do other things. I find it difficult sitting, listening to music before my mind wanders or I get bored since I’m a dirty millennial with a tiny attention span. One of the few artists I follow - religiously - is Bruce Springsteen. It’s a well documented phenomenon, his legendary concerts closer to evangelical events, inspiring a maybe not as visible, but possibly more passionate fandom than many others today, one which only an artist with forty plus years experience can cultivate. It goes beyond just liking his songs, they bury into you and can move your very soul. There’s even another movie coming out, ‘Blinded By the Light’ with the inspiration the Boss’ songs can evoke at its heart. It’s been a good few years for Boss fans, first his autobiography followed by the record breaking Broadway show it spawned proving, as if it needed to be, that he must be one of the most naturally gifted storytellers ever. It’s rare to encounter someone with the talent of making the specific so universal, placing you in a scene you can picture, even feel, with only a few words. Sometimes I hear a lyric and think “that’s so good, why do even bother when nothing I write will ever come close?” Most recently was his latest album, Western Stars. His fourth ‘solo’ album is a collection of ballads tied around the American expanse and the loneliness and beauty that comes with it. There are more upbeat numbers like ‘Tucson Train’ and ‘Sleepy Joe’s Cafe’, and more sombre, orchestral tracks like ‘Chasin’ Wild Horses’ and the titular ‘Western Stars’. For me, it’s good but as yet hasn’t made much of an impression. Coming back to how I passively listen to music, the tunes, bar a few, don’t immediately sear themselves in your memory, which makes it harder to fully engage with the lyrics. The characters are good, but a bit more removed from my experience, with I think some of the country music elements not translating as well to a city slicker in the UK. Still, it was better than the last studio album we were treated to, High Hopes, five years ago. More Springsteen music is always a good thing, and with it comes the excuse to delve into his back catalogue, again. Here’s my top five Bruce Springsteen albums, listed in the order they were released.

Born to Run What an album, a mix of fun, catchy tracks and sweeping epics, all bursting with youthful ambition, potential, anticipation and dreams of great things to come. I’m older than Springsteen was when he wrote this, which is a real existential trigger. Standout Track - It could really be any of them, but for the beautifully simple opening to the defiant crescendo, it has to be Thunder Road. Darkness on the Edge of Town An album I only realise the brilliance of the more I listen to it. A more mature and sedate follow up to Born to Run, with the beginnings of Springsteen’s knack for capturing the resilience and nobility of the downtrodden, everyman working class. Standout Track - Depends on my mood, but as a tiebreaker it goes to the catchiness of The Promised Land. Nebraska In my view his best for writing and imagery. Totally different from everything he’d done before, but they land just as powerfully even without the backing of the E Street Band. Delves into the darkness of the human psyche, but tempered with the hope for something better. Standout Track - Tough choice, but for doing so much scene setting with so little, and the deeply personal message for him, My Father’s House. Born in the USA The album that made him a phenomenon, and for good reason. Springsteen himself considers it a collection of leftover tracks from other sessions, but what tracks. Every one is a straight up classic, from fun and frivolous to dark and brooding. Standout Track - Deeper than it first appears and, if the legend is true, the best example of doing your work the night before a big assignment, it’s Dancing in the Dark. Wrecking Ball This is my curveball, which while not as roundly praised as other works, has a number of top notch tracks, and you feel the anger against those who caused the Financial Crisis in his second album directly related to current events (after The Rising, my number six). Also probably came at the right time for me, when I was in the real swing of Bossmania and saw two shows on the tour. Standout Track - Though cheesier than other songs, the ebb and flow of good times and bad makes my pick the titular Wrecking Ball. |

Archives

June 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed