|

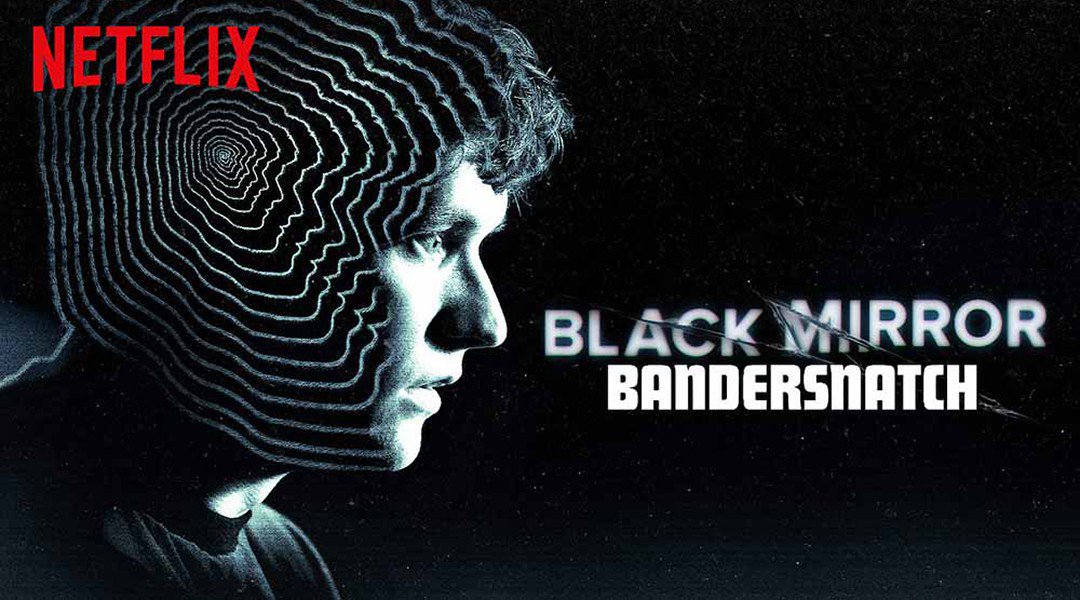

*Spoilers for Bandersnatch. When starting up Netflix’s latest flavour of the moment, Bandersnatch, and its cutting edge twist of you, the viewer, choosing your own adventure (or “branching narratives” as the Choose Your Own Adventure publisher’s lawyers prefer) my first impression was, “So it’s a live action video game?” I expected a serviceable story secondary to its technical gimmick. However as to be expected from Charlie Brooker and the Black Mirror team, what they have done is much smarter. Black Mirror has an excellent level of quality control, there being no out and out bad episode in its four seasons plus specials, and has become famous for its examination of the relationship between humans and technology. Here the relationship is even more intimate since it is literally you, personally, interacting with the story. And boy did Bandersnatch make me think myself a fool for preemptively dismissing the story, for it’s not secondary to the technical gimmick, it is intrinsically entwined with it. In video games and the Choose Your Own Adventure books, you inhabit the character, making decisions good or bad, and dealing with the consequences. In Bandersnatch, you ARE a character. The protagonist, Stefan, is aware of his lack of agency, being forced to enact your whims to the extent where he will challenge you to reveal yourself. You are then able to introduce yourself to him as Netflix which I laughed so hard at I nearly missed the next choice. The results of the multiple choices are also woven into the narrative, and failure is encouraged, indeed sometimes necessary, as what you learn in one branch helps you progress in other branches. When you do fail it takes you back to where you should make a different choice, but the characters carry at least some knowledge of the previous storyline. This leads one character, admittedly tripping on acid, to jump off a balcony in the expectation of respawning. They are then absent from future storylines. However with all these competing strands it does get a bit muddled in parts. The premise is of Stefan, a computer programmer, going mad as he codes a new choose your own adventure game, so this confusion is a plus, at least on your first watch/playthrough. It becomes much more of a grind if you want to unlock all the endings, since introducing yourself as Netflix is much less amusing the fifth time than it is the first. One of the benefits of it being a standalone, two hour story is that the endings can be vastly disparate, unlike some video games which have to reign back in sometimes dozens of choices to the storyteller’s predetermined endgame. The conclusions range from ‘he went back and died as a child’ to ‘it was all a drama on a film set,’ however such thematically different outcomes make you less sure what to think of the common beginning they shared. Does he as a deluded actor exist in a universe with time travel, or was the point of it all just to be cool? It’s all very clever, and that may be a drawback of using the viewer as a separate entity, you never fully connect with the characters. They’re more like toys in a sandbox you can mess around with, and unlike video games there’s nothing beyond binary choices or internet mined easter eggs to keep you coming back. It loses one of the most important parts of choice - consequence. Gamers certainly know all about consequences, as it is our own actions that lead to success or another broken controller. One game that did branching narratives very successfully recently was Until Dawn from Supermassive Games. The characters were actually live acted and then animated into the game world, including photorealistic Rami Malek and Peter Stormare. It had a schlocky horror premise, a group of unrealistically sexy teens go to a remote cabin and bad things happen. While you never connected with these murder-fodder either, it had gameplay between the choices and some of the branching narratives even depended on how you performed in these action sections. As well as drama, it also gave you the challenge of keeping these eight sexy teens alive until the end - or killing them, whatever floats your boat. On the other end of the spectrum, where gameplay mostly existed to ferry you from choice to choice are the games from interactive narrative gurus Telltale Games. Playing characters as diverse as a fairytale town sheriff, a queen’s handmaiden and Batman you were placed in their shoes and had to carry conversations and make often hard decisions. The signature “So and so will remember that,” that appeared on screen after sometimes seemingly innocuous conversation choices was a common cause of anxiety.

The one that connected most with players and left many a blubbering mess was Season One of The Walking Dead. In it you play Lee, an escaped convict who develops a bond with an orphaned girl, Clementine, in the middle of a zombie apocalypse. It worked because you didn’t feel as though Lee had to keep Clementine safe, YOU had to keep Clementine safe. The dialogue, character beats and the frequently traumatising decisions you made and then had to respond to made you connect with these characters in a way very few games do, and mostly through simple multiple choice dialogue options. The ending is still one of the all time gaming tearjerkers. - Ironically as Bandersnatch is touted as new and innovative, Telltale went bust last year, in part due to audience fatigue with the genre (as well as being an apparently terrible place to work). Of course none of these multiple choice flowcharts are truly a choose your own adventure, in the way only the likes of D&D can be. They’re more a choose which path from the writers you want to explore, but that little bit extra interaction, used right, can make a difference. Bandersnatch was a fun experiment, and its approach was spot on. Had it been just another basic story it surely would’ve made no impact, but since it subverted the genre in a new way I’m recommending it to my other skeptical gaming friends. Brooker, himself an ex-games reviewer, has said it was originally going to have a puzzle at the core, which I think it may need if there was ever to be another. I appreciate trying to bridge the gap between film and video games, but I wonder how far they can really go before you’re just as well playing a video game.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed